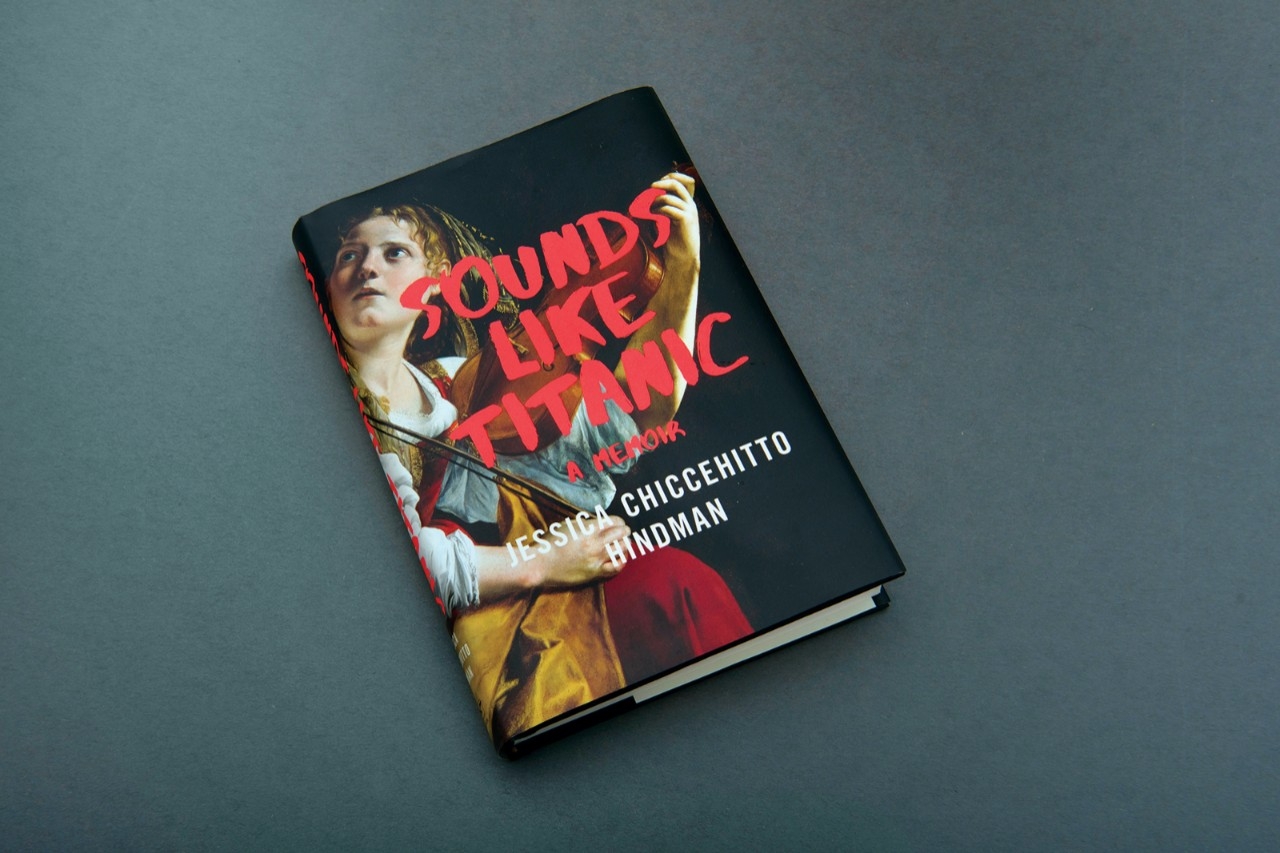

Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman, a professor of creative writing at Northern Kentucky University, stands quietly behind the podium at Joseph-Beth Booksellers in Cincinnati, Ohio. She’s there to read an excerpt from her new memoir, “Sounds Like Titanic,” but, for now, she’s enjoying the looks on the faces of those in attendance.

Minutes before Hindman stepped forward, Tamaiya Wilson, a professional violinist and NKU alumna, performed for the crowd—not playing the violin but, rather, miming on her instrument to a CD of music suspiciously similar to the score from 1997’s “Titanic.” It was a bizarre scene, but this was no avant-garde art-piece. Instead, it’s a ruse—one Hindman knows all too well.

At one point in her life, Hindman was a fake violinist, too. And she’s spent years trying to make sense of the experience.

WEST VIRGINIA, 1985

The daughter of a doctor and a social worker, Hindman grew up in two small, Appalachian towns in West Virginia (until she was 10 years old) and Virginia (through high school).

And though there’s plenty of fakery in her story, one thing is very true: She loves the violin and has since she was 4 years old,when she fell under the spell of Vivaldi’s “Winter” while watching “Sarah and the Squirrel,” a 1982 animated film about World War II that featured the composition. For four years, Hindman begged her parents for a violin. She dreamt of becoming a professional violinist and mentally played the few Vivaldi notes she could remember before falling asleep each night.

Then, shortly after her eighth birthday, Hindman’s parents caved. They bought her a violin and committed to driving several hours both ways through the mountains to Virginia for weekly lessons. Through high school, she dedicated herself to playing the violin, and locals in her hometown took notice. They told her she had a “reeyell” gift.

NEW YORK, 1999

Hindman’s gift earned her an acceptance letter from New York’s Columbia University. Her parents pleaded with her to turn it down, but she was eager to leave Appalachia for the Ivy League. She enrolled as a music major and packed her violin for the move to Manhattan. Growing up in a doctor’s household, Hindman was aware of class differences between her family and others in the community. But when she got the $30,000 price tag for her Columbia education—an amount her family could not afford—her elevated standing flipped upside-down.

“I found myself coming from a town in which I was a doctor’s daughter… to going to an Ivy League school where I was seen as poor,” Hindman says. “I was privileged in one world and not in another.”

Hindman had convinced her family she could get a job to make up the difference in tuition cost, but, determined to become a professional violinist, she didn’t have much time for work. So, to afford her first semester of college, she sold her eggs to a fertility clinic.

But while years of dedication and private lessons can make you the best in your small town, they don’t automatically lead to professional musicianship. Surrounded by more talented violinists, Hindman barely made the cut for the college orchestra. After a few months, Hindman decided to face the music and changed her major to Middle Eastern Studies.