“The most gratifying thing is watching them grow and creating a real, successful musical experience because you positively motivated them, created opportunities for them, pushed them.”

A LIFE-CHANGING DIAGNOSIS

By 2011, at the age of 50, Karrick was at one of the highest points of his career. He had racked up a list of credits that any musician would envy, and bands had performed his compositions all across the globe. However, days before he was set to attend The Midwest Clinic in Chicago as a guest conductor, he was sitting in a hospital bed.

“It was a form of pneumonia called pleurisy, where your lungs fill up,” Karrick says. “They eventually had to tap into my lungs to drain them.”

After a two-week hospital stay, Karrick bounced back but later began bleeding and bruising easily—a sign that his platelet count was going down. Despite trying many different treatments, nothing helped. In February 2014, Karrick’s oncologist noticed a lump on his neck. After a biopsy, Karrick was diagnosed with Stage 4 Hodgkin’s Lymphoma that had started attacking his lymph nodes, pelvis and bone.

“My doctor said that if you have to have cancer, that’s the one you want to have,” he says. “It’s the most predictable.”

Karrick spent the next six months undergoing chemotherapy treatments. He lost all of his hair and developed dystonia, which is a movement disorder that causes your mouth muscles to contract involuntarily. He’s no longer able to play the trumpet, but he finds love for music in other ways with writing and composing regularly.

“I had an embouchure—all of the instruments have this muscle formation and lip formation needed to play. After the first round of chemo, it destroyed something. A lot of brass players get it,” he says. “I really can’t get a sound out. I haven’t really tried to play the trumpet since May 2018, but I play a lot of piano and perform regularly with rock, jazz and soul bands. You just roll with the punches.”

One year later, Karrick was in remission. But then his platelets started sinking again. This time, the damage from the chemotherapy was the reason. Karrick was then diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), formerly known in medical circles as preleukemia. The cure? A bone marrow transplant.

TAKING TIME OFF

Karrick knew his transplant would happen a year in advance. And he also knew the long-term risks.

“There is a 60 percent survival rate for these things. Doctors lose every four out of 10 patients,” he says. “But if I didn’t do the transplant, everything would have shut down eventually.”

Neither his siblings nor his four children were a match, so he registered with Be the Match, a global registry that connects patients with bone marrow or stem cell donors.

“I really want to encourage Americans, especially underrepresented populations, to consider being a donor,” Karrick says. “There is a serious lack of available donors.”

Before Karrick was admitted to Cincinnati Jewish Hospital on July 17, 2018, he experienced a series of tests and procedures to assess his general health to make sure he was physically prepared for the transplant.

“Jewish Hospital is one of the top places in the country for bone marrow transplants,” he says. “Their results are on par with the top places in the world.”

Karrick’s surgeon implanted an intravenous catheter—a long, thin tube commonly called a central line—into a large vein in his chest to infuse the transplanted stem cells, medications and blood products into his body. And then it was time to get started. After the pre-transplant tests and procedures, Karrick experienced conditioning, a process that destroys cancer cells, suppresses your immune system and prepares your bone marrow for new cells.

“They gave me powerful chemotherapy for four days in a row. It kills everything in your body—bone marrow, immune system, everything. Then you rest for a few days,” he says. “A week later, you watch as all your numbers go down to zero.”

A week later, on July 24, the donor’s stem cells were infused into Karrick’s body through a central line. When the new stem cells entered the body, they traveled through the blood to the bone marrow. Over the course of several weeks, those stem cells began to multiply and make new, healthy blood cells, which is known as engraftment.

In the days and weeks after Karrick’s transplant, he remained under close medical care at Jewish Hospital. Three weeks later, he made it home just in time for his 58th birthday.Even though Karrick was released from the hospital, he had daily blood tests to monitor his condition and make sure the donor cells grafted with his body. Lucky for Karrick, he had support at home.

“When you go through this transplant procedure, you can’t go at it alone,” he says.“I couldn’t drive. My primary caregiver was—and is—my wife Carole. It was a big sacrifice for her to make. Our house is 23 miles away from Jewish, and she spent every day single day with me at the hospital.”

Karrick, grateful for a second chance at life, is 100 percent engrafted.

“I was lucky to have really good doctors. I’m here because of science,” he says. “It changes a lot of your perspective on life. I don’t know how much time I have left on this earth. You appreciate nice days a little bit more. You appreciate good times. I found myself a lot less tolerant about time that gets wasted. A lot of stuff that might have been important before just isn’t anymore.”

COMING BACK TO WORK

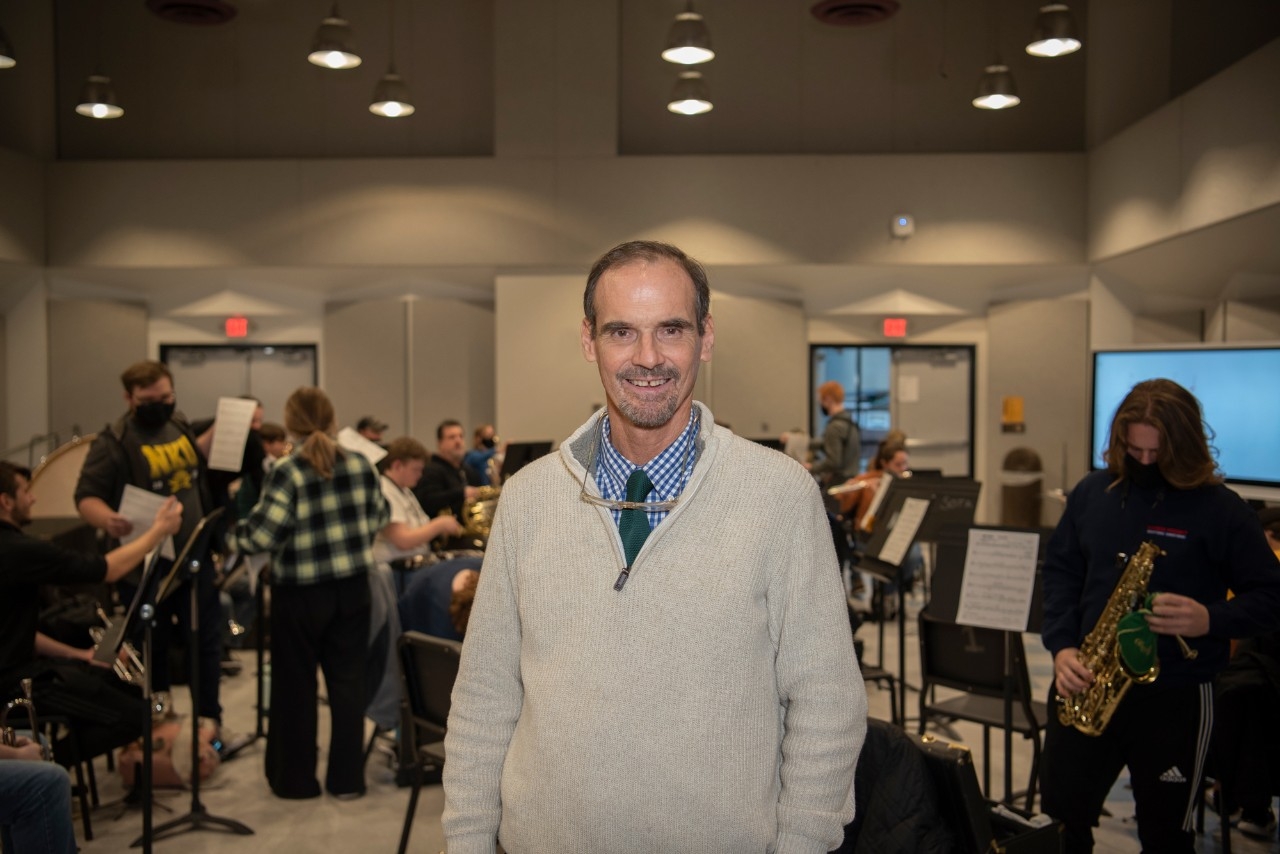

Karrick had a bit of an unconventional return to NKU after his bone marrow transplant. He came back to campus in the fall of 2019, just a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the U.S. He taught for a few months in person, and then everything went virtual.

Despite the many setbacks throughout the last decade, Karrick is dedicated to teaching. For the last 38 years, the students keep him coming back to work—even onthe hardest days.

“My juice for coming in every day is student growth,” he says. “I’m not the most popular or well-liked professor because I’m really honest with my students and tend to be a little brash at times. The most gratifying thing is watching them grow and creating a real, successful musical experience because you positively motivated them, created opportunities for them, pushed them.”